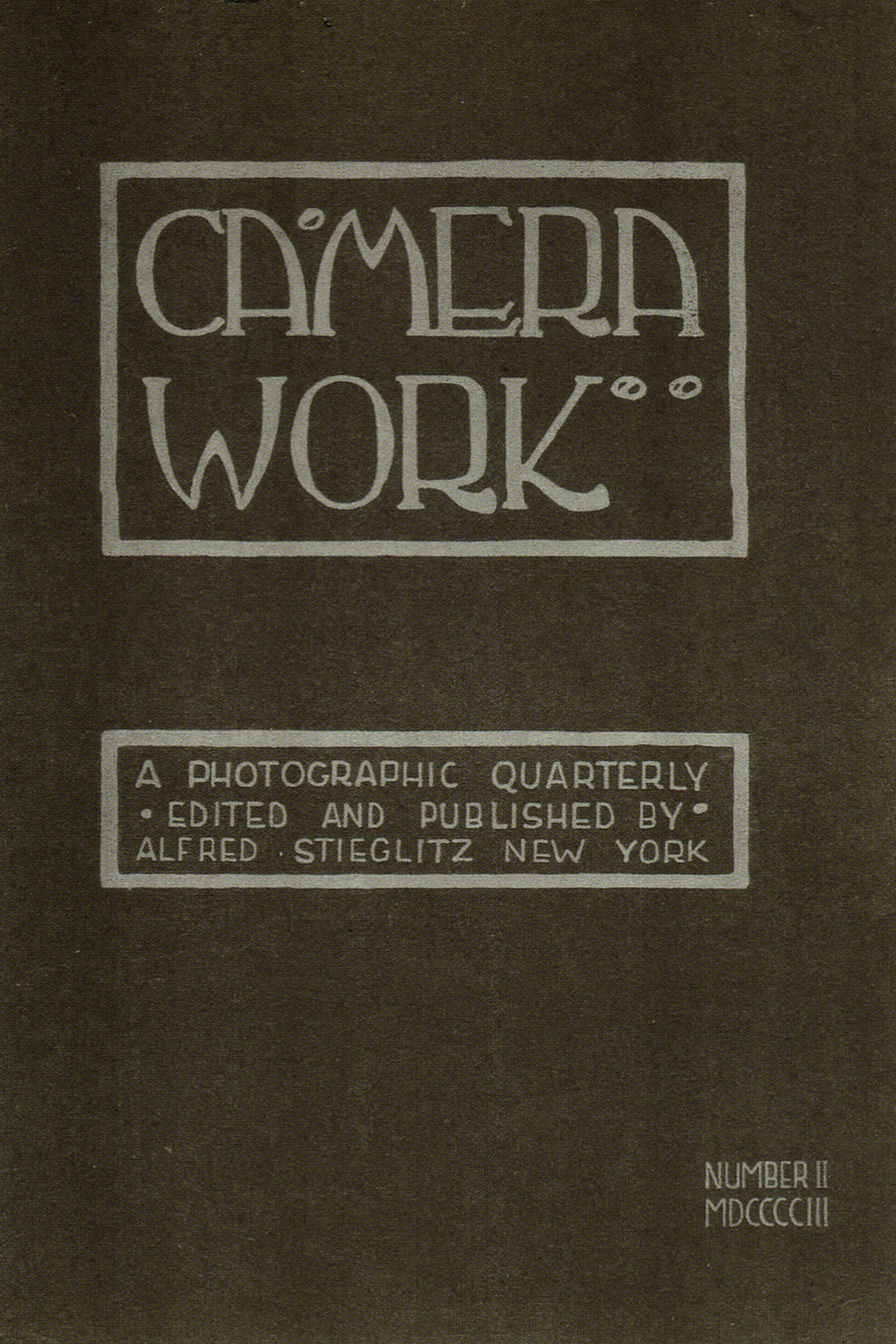

CAMERA WORK, published between 1903 and 1917 by Alfred Stieglitz, and perhaps the most important arts magazine of the early 20th century. In its 50 issues essayists and artists pronounced on the rapidly evolving world of art and photography. The work of key new artists from both sides of the Atlantic, John Marin, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Rodin, Marius De Zayas, and others, was represented. In fact, artists such as Matisse appeared in Camera Work several years before the celebrated Armory Show of 1913.

Stieglitz, founder of the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession (1905-8) and its successor, Gallery 291 (1908-17), saw the need for a journal that would celebrate photography as a fine art ; indeed, an art that, as with painting, sculpture, and music, would inevitably evolve with time. He had founded or edited several earlier journals, American Amateur Photographer and Camera Notes, but in each of these he had encountered resistance to his ideas.

Camera Work became a forum for lively criticism and debate about not only photography but the arts in general. R. Child Bayley, Robert Demachy, Frederick Evans, Sadakichi Hartmann, George Bernard Shaw, and Edward Steichen were among the many who contributed opinion pieces; Gertrude Stein's first writing appeared in the journal. The images presented in Camera Work were meticulously printed, making it unique in the world of periodicals. Detailed descriptions of the techniques used to produce them were also included.

It is significant that the last issue of the journal (49/50, June 1917) introduced the radical work of Paul Strand.

— Tim TROY

+ J. GREEN, Camera Work : A Critical Anthology (1973)

Mental Reactions—by general accounts the earliest example of visual poetry in America—is the original maquette for a printed version published in the avant-garde magazine 291. Both a drawing and a poem, the work is a collaboration between the Mexican-born caricaturist Marius de Zayas (1880–1961) and the American journalist and art patron Agnes Ernst Meyer (1887–1970).

De Zayas left Mexico for New York in 1907 and within two years was exhibiting at Alfred Stieglitz's Fifth Avenue gallery, known as 291. Defining himself as a "propagandist for modern art," de Zayas helped arrange Pablo Picasso's first United States exhibition—a show held at 291 in 1911—and a pioneering exhibition of African sculpture at the same gallery in 1914. On visits to Paris in 1910 and 1914 he met the most advanced artists and writers working in Europe, including Guillaume Apollinaire—French poet, critic, and editor of the review Les Soirées de Paris—whose calligrams, or visual poems, had a powerful influence on him. Writing to Stieglitz from Paris in July 1914, de Zayas enthused: "[Apollinaire] is doing in poetry what Picasso is doing in painting. He uses actual forms made up with letters. All these show a tendency towards the fusion of the so-called arts." Apollinaire published four of de Zayas' caricatures in Les Soirées de Paris in 1914, and the following year de Zayas published one of Apollinaire's calligrams in 291, introducing the newest synthesis of word and image to an American audience.

Another member of the Stieglitz circle visiting Paris that July was Agnes Meyer, whom de Zayas took to see Picasso's latest works. Returning to New York after the war broke out, Meyer and de Zayas joined forces with Stieglitz and the French businessman and photographer Paul Haviland, another Stieglitz associate, to found the magazine 291. Its second issue featured a full-page printed version of Mental Reactions, in which Meyer's poem, cut into individually trimmed blocks of pasted-down text, is literally strewn across the page. De Zayas' bold, cubistlike composition lends structure to the whole, but for readers there is no single or prescribed direction. We begin at the upper left and confront, as the text descends, multiple pathways and multiple readings. The poem records the random musings and doubts of a woman torn between an illicit romance ("why cannot all the loves of all the world be mine?") and dutifulness ("Their bed-time. / They will want to say good-night. / I must go."). While 291 was hardly a feminist journal, it was sympathetic to women's causes and receptive to examining the female identity and condition.

Mental Reactions represents an early chapter in the history of DADA. To reach a broader audience, de Zayas sent copies of 291 to vanguard artists in Europe, including Tristan Tzara, a leader in the emerging Dada movement. Tzara, in turn, sent publications to de Zayas, making him the conduit for Dada ideas in New York. De Zayas was never a member of the Dada group, and the scholar Francis M. Naumann has rightly pointed out that he would have rejected its nihilism. Nonetheless, innovative works such as Mental Reactions were known to the dadaists in Europe and are part of DADA's larger history.

Agnes Ernst first met Alfred Stieglitz and the 291 circle in 1908, when she was an enterprising freelance reporter for the New York Sun. After marrying the wealthy financier Eugene Meyer two years later, she became an avid art collector and a generous patron. Eugene and Agnes Meyer donated important works to the National Gallery beginning in 1958, including paintings by Paul Cézanne and Edouard Manet, sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, and watercolors by John Marin. Agnes Meyer was the mother of Katharine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post and recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for her autobiography, Personal History.

www.cargillcontemporary.com/papers/291/

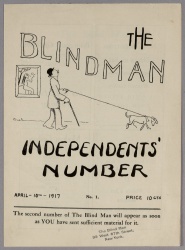

Marcel DUCHAMP, Henri-Pierre ROCHÉ & Beatrice WOOD (Éd.). The Blind Man, numéro 1, New York, 10 avril 1917

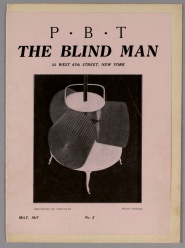

Marcel DUCHAMP, Henri-Pierre ROCHÉ & Beatrice WOOD (Éd.). The Blind Man, numéro 2, New York, mai 1917

Marcel DUCHAMP (Éd.) Rongwrong, numéro 1 (unique), New York, 1917

Francis PICABIA (Éd.), 391, New York, 1917