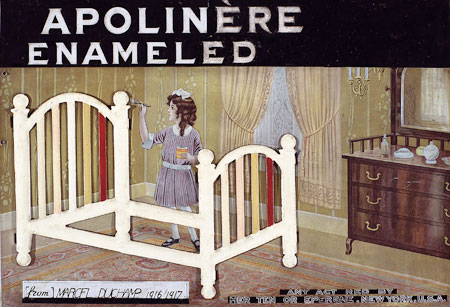

Marcel DUCHAMP. Apolinère Enameled, Ready-Made rectifié, publicité pour les peintures sapolin enamel, tôle peinte, 24 X 34, New York, 1916-1917, Philadelphie, Museum of Art

Marcel DUCHAMP. Apolinère Enameled, Ready-Made rectifié, publicité pour les peintures sapolin enamel, tôle peinte, 24 X 34, New York, 1916-1917, Philadelphie, Museum of Arthttp://www.toutfait.com/issues/issue_3/Collections/rrs/p_7a.html

Original Version:

1916-17, New YorkPhiladelphia Museum of ArtThe Louise and Walter Arensberg Collectionpencil and paint on cardboard and painted tinrectified readymade24.4 x 33.9 cm

By simply making several alterations and signing this ad, Duchamp turned an ordinary, everyday advertisement for a product seen in the shop window into a piece of art. The original version of this work is inscribed on the lower left: "[from] Marcel Duchamp 1916 1917." By including the "[from]" before his signature, as he does in a number of Readymades, Duchamp plays with the concept of authorship. He acknowledges that the piece came 'from' him and was not 'made' by him, but still signs it and calls it art nonetheless.

In pencil on the back of the original piece, a manufacturer's label states "If sign becomes soiled, clean with damp cloth." Duchamp added the following ironic twist to this standard, practical advice: ": Don't do that" In this way, he stands to challenge such practical advice.

Originally an ad sign for the industrial paint Sapolin Enamel, this piece was altered in several ways, thus rightfully earning a categorization of rectified readymade. Before such alterations need be addressed, however, it should be mentioned that not all scholars are in agreement as to the brand of paint whose advertisement this is. In a sea of assertions that the ad is for Sapolin Enamel, Ramirez claims in his recent text that the brand is "Ripolin," not "Sapolin" (41). The reader has to wonder as to his source, and likewise begin to question all of the interpretational and critical claims made in reference to Duchamp's work on the whole. What is the truth? In the end, it depends on who is writing, who is reading, and who is believing. Duchamp claimed it was a Sapolin ad in his Apropos of Myself in 1964, but since when has he been straightforward in his comments? Having learned from experience, one should be more tempted to disbelieve than accept Duchamp's claims.

Duchamp made the following alterations to this advertisement:

1. In order to make this piece a homage to his friend Guillaume Apollinaire, the artist changed the large white block letters of the title from "Sapolin [or Ripolin for argument's sake] Enamel" to "Apolinere Enameled." He cleverly accomplished this by blocking out certain letters and adding others. And so, this piece illustrates Duchamp's linguistic experiments with French and English during his first sojourn to the United States (Schwarz 194). It seems very Duchampian that in an interview the artist once allegedly admitted that in fact he wasn't all that close with Apollinaire.

2. Duchamp also broke up the manufacturer's name and city, originally reading "Gerstendorfer Bros. New York, U.S.A.," into a series of nonsensical disconnected words: "Any act red by her ten or epergne, New York, U.S.A."

3. Aside from his addition of a signature in the bottom left, Duchamp added a mirror reflection of the young girl's hair in the mirror above the chest of drawers. Many interpret this intentional addition of hair to the image as having sexual connotations.

The subject matter of this piece is very erotic overall. The central image of the bed is a classic symbol of sexual intercourse. Ramirez also notes that the girl painting the bedpost has overtly sexual connotations in its suggestion of a female caressing a male phallus (42).

Varnedoe links this Readymade with the later Readymade Belle Haleine, noting that Apolinere Enameled's idea of the "private advertisement" later yielded Duchamp's own "house brand" Belle Haleine (272). Mink notes the pieces connection with yet another Readymade, In Advance of the Broken Arm, explaining that when "Apolinere" is pronounced with an American accent, it sounds like "A pole in air" (92).

Replicas:1) 1939, ParisPhiladelphia Museum of ArtThe Louise and Walter Arensberg CollectionPrototype for reproduction in The Box in Valise, 1941 (cat. No. 484)Photo with pasted-paper cutout of bed frame and vertical bars hand-colored by Duchamp (colors of background and vertical bars differ form orig.)(16.8 x 24.3 cm)

2) April 1965, MilanCollection Arturo Schwarz, MilanProof of Galerie Schwarz edition, 1965 (23.5 x 33.8 cm)Inscribed on back by Duchamp, in French in black ink: "I think the original metal sheet has a border (about 4 mm)(it doesn't matter if it's going to lead to complications) running right round it. OK: color of 2nd bar correct - in any case, it's all right by me. The whole scheme comes off very well as regards colors and their value. Inscribed on back in red ink: "bon a tirer/ Marcel Duchamp/ 27 avril 1965"

3) 1965, MilanEdition of eight replicas, identical in size and characteristics to orig., made under Duchamp's "supervision"Inscribed on upper left on back in red ink: "Marcel Duchamp 1/8-8/8"On back of small copper plate, upper right: "Marcel Duchamp, 1965, 1/8-8/8," engraved on bottom of plate: "Apolinere Enameled 1916-17 / EDITION GALERIE SCHWARZ, MILAN"Two replicas outside edition reserved for artist and publisher, and two more for museum exhibition

http://www.toutfait.com/unmaking_the_museum/Apolinere%20enameled.html

***

The commonplace objects that Duchamp chose as "Readymade" works of art epitomized the artist's belief that art should go beyond the visual and appeal to the mind as well as the senses. Duchamp began signing and giving titles to mass-produced items after he moved to New York in 1915, beginning with a snow shovel purchased in a hardware store. With Hidden Noise marks the transition from Duchamp's signed objects to more elaborate works, which Duchamp called "assisted Readymades."

Another assisted Readymade, Apolinère Enameled, was a humorous homage to his friend the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. The tin sign, which Duchamp probably obtained from a paint store, was an advertisement for Sapolin enamel, a brand of industrial paint commonly used on radiators. The artist carefully manipulated the lettering in the commercially printed plaque, obscuring the S in Sapolin and adding new letters in white paint to evoke the poet's name, albeit intentionally misspelled. Duchamp also delicately shaded in pencil the reflection of the little girl's hair in the mirror. Twentieth Century Painting and Sculpture in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (2000), p. 48.

http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51563.html

Another assisted Readymade, Apolinère Enameled, was a humorous homage to his friend the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. The tin sign, which Duchamp probably obtained from a paint store, was an advertisement for Sapolin enamel, a brand of industrial paint commonly used on radiators. The artist carefully manipulated the lettering in the commercially printed plaque, obscuring the S in Sapolin and adding new letters in white paint to evoke the poet's name, albeit intentionally misspelled. Duchamp also delicately shaded in pencil the reflection of the little girl's hair in the mirror. Twentieth Century Painting and Sculpture in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (2000), p. 48.

http://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51563.html